Dead metaphors. Every English student should be aware of them: little zombie bits of language that once had a life all of their own, but now wander near and far, open-mouthed, vacant.

Metaphor, as your English teachers will hopefully have taught you, makes speech and writing vivid. It carries over meanings or concepts from one area of knowledge to another, giving life to the unfamiliar in terms of the familiar.

So, to explain, I used a metaphor at the beginning of this article: I compared Dead Metaphors to zombies, speaking about something perhaps a little unfamiliar to you (dead metaphors) in the terms of something more familiar (zombies).

Over time, however, these new figures of speech– these metaphors– themselves become familiar through use. They no longer surprise or delight. The original life of the metaphor seeps away.

Ultimately you’re left with a word or phrase that is either a cliche (“I’m over the moon”, says the footballer without thinking, meaning he is delighted) or something that has become so common or familiar that you don’t even think of it according to its original metaphorical meaning anymore (“can you grasp that?” says the English teacher to her student).

So why the waffle about dead metaphors?

Well, the word ‘undermining’ is a dead metaphor. Today most people don’t think twice about the word when they use it. In everyday speech, of course, it means to secretly weaken someone– but we never think about where the word came from. That’s natural: dead metaphors are everywhere and if we stopped talking every time we used one, we couldn’t hold a conversation.

Once upon a time, however, to talk about one person undermining another person would have been a vivid, threatening use of language.

Undermining, in its original sense, meant to build a mine underneath something– say, a wall– and to use that mine to destroy the object. Mining has been used by the military since ancient times, but undermining became an important military tactic in the middle ages. Besieging armies would build tunnels underneath castle turrets, undermining the foundations of otherwise impregnable towers. They would then build fires (or, later, set off explosives) that would bring the mine down, and the castle walls with it.

That’s what undermining was: the way to secretively bring down a city or citadel. The first time someone said, “he’s undermining her” or “they are undermining us” must have been a striking use of speech. So striking, in fact, that someone listening repeated the metaphor– as did the next person. Or, perhaps, this figure of speech occurred to a number of different people as this frightening technology became more and more familiar to people. Ultimately everyone understood it in its new sense: to secretly weaken another person or thing.

We very often think of the First World War as a war of innovations in technology, of the shock of the new. Yet it is a striking fact that because 1914-18 was a static war of trenches and fortifications, this old military technique of undermining the enemy experienced a grim resurgence.

Today we’re going to take a look at a remarkable and horrifying example of undermining that took place during the First World War.

At the start of the summer it was announced that a new and extensive archaeological dig is to go ahead, mapping what is known today as the Lochnagar Crater. The Lochnagar Crater was created by what was the largest ever mine ever exploded.

The explosion took place on the first day of the Battle of the Somme– July 1st, 1916. The Somme has today become a kind of shorthand for a battle with massive loss of life for little obvious gain. Yet as the Somme began there were high hopes that this was the battle which, after the terrible failures of 1915, would lead to movement on the Western Front. A massive attack was to take place on German lines around the river Somme, in the hope of both breaking through those lines and so relieving pressure on the French army at Verdun.

The attack on the German line near La Boisselle was to be led by three British Brigades, part of the 34th division. Two were ‘Pals’ brigades– the Tyneside Scottish and Tyneside Irish– raised from Irish and Scottish Communities in the North-East. The third, the 101st Brigade, was amalgamation of different companies and regiments that included the Grimsby Pals and other fighting units.

The German trenches had sustained a week of incessant bombardment from British artillery in the run up to the first day of the Somme. This alone was expected to have decimated the German defences and demoralised the soldiers sheltering below. Yet, in addition to this form of attack, the British generals wanted to punch a hole in the German line, and to do this they planned to explode a massive pair of mines beneath the German dug outs. The Royal Engineers were employed to dig beneath and undermine the German defences– setting 27 tons of high explosive to go off before the attack. In fact, 28 Royal Engineers were actually killed when the explosives went off at 7.28 on the morning of the 1st.

The explosion of the mine was devastating. It lifted the French earth and all those sheltering within it in a massive column 1,200 metres into the air. When the air cleared, what was left where the German dug outs had been was a crater 120 metres wide (that is, around twenty metres longer than a football pitch) and 20 metres deep.

You might think that what we today call the ‘shock and awe’ of such a massive explosion would alone result in a British victory in this sector of the battle of the Somme. What followed, in fact, was a disaster for the attacking British troops. The German trenches had been dug deep and those in them had been well sheltered from the hellish bombardment in the week prior. The many German soldiers who had not been killed by the mine explosion simply took their places again in the line once the British artillery ceased (allowing the British soldiers to go ‘over the top’).

The British infantry, doubtless expecting minimal resistance, calmly advanced in long lines– as they had been trained– into devastating machine gun fire. Over 6,000 British soldiers died in the attack for the slightest gain in ground. It is, in its own way, a typical story of the disastrously planned and bloodily fought first day of the Somme.

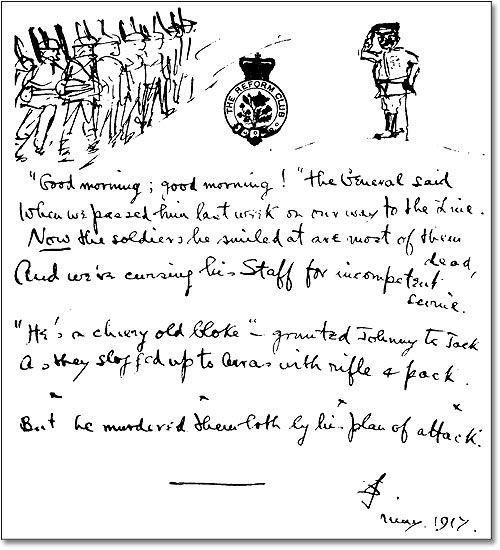

You can find out about the new archaeological exploration of the site and the hidden tunnels that run warren-like through the area by linking to this BBC Radio 4 Today news report. It’s clear that even those experienced archaeologists who have begun the task of finding the remains of humans and human activites underground are deeply moved by what they’ve found. You can also read an excellent report on the BBC website about the attack, ‘WW1 underground: unearthing the hidden war’, that contains an TV interview within one of the actual tunnels with historian Simon Jones, explaining what life was like as a miner. As a literature student, to get a sense of the claustrophobic horror that an ordinary soldier experienced in tunnels beneath the battlefields, you should read Siegfried Sassoon’s grim poem ‘The Rear Guard’ (found in the Stallworthy anthology if you are an AQA AS student). You can, of course, find my notes for this poem on Move Him Into the Sun: though as the poem is still in copyright, I can’t reproduce the actual text here. The events of Sassoon’s poem take place near Arras, not La Boisselle, but give a flavour of the sense of recoil a non-miner felt about these tunnels far underground.

Today, what came to be known as the Lochnagar crater is now a privately owned memorial that you can visit– and you can find its website here. The website provides shocking footage of a similar mine being let off at the Hawthorn Redoubt (pictured above) and its terrible effects. It’s a chastening lesson in the extreme violence all too common during the First World War. The word ‘undermining’ may never mean quite the same thing again.