Onward, into a disturbing account of one of the most wretched episodes in the wretched history of warfare. Chapter Four:

Summary

Months have passed at the front and Willie is upset that Gretta has not responded to his letters. He writes to her declaring his love, and retains the hope that she loves him too, but feels more and more angry and humiliated by her lack of reply. Before leaving Gretta, it transpires that Willie has asked her to marry him, and she refused. He once understood the reasons for her refusal, but longing for her without remittance, he writes short letters that veer between lumpen description of life in the trenches and blurted declarations of love. Writing in this way sharpens his self-consciousness and anxiety.

It is now spring and the Fusiliers decamp to a section of line near the village of St Julien. The men relax somewhat, skinny dipping in the river together and playing football. They find a joy in their momentary leisure together, though the noise and bustle of the front is near. Disarmed and naked, they talk frankly at the riverside; amidst the aimless chatter Captain Pasley speaks of his worries about the manning of his father’s farm at home.

Soon the men are back in the line. They first make it their business to tidy a trench once badly kept up by French soldiers. They settle into a time of distracted dull fear there, until the day when, as Captain Pasley censors his men’s letters home and the platoon are relaxing after a satisfying meal, Christy Moran sees a strange yellow cloud floating over no-mans land.

It is a German gas attack, but the men do not know this. It is an inexplicable sight as it advances towards them. At first the fusiliers fire into the yellow fog, but cease firing when there is no sign of an advancing enemy. The lieutenants consult their commanding officers, who are as nonplussed as their subordinates. The fog eventually reaches an Algerian trench to the platoon’s right. Screams of torment there prompt Pasley to the thought that the smoke is poisonous. The fog reaches the Dublin fusiliers’ trench and inspires panic as Irishmen, like the Algerians, begin to die. Christy Moran asks for permission for the company to retreat, but Pasley declares he has no orders to allow it. As the chlorine begins to fall into their section and men die in the trench, Pasley assents to withdrawal, but refuses to move from his post. Willie and the still-surviving men climb the parados and run for their lives amidst the general terrified scatter, every man for himself. Officers behind the line stand confused by the soldiers’ sudden, mysterious capitulation. Eventually, Willie finds himself in the air beyond the gas, and collapses.

He awakens to the aftermath of the attack. Blinded men move in lines. The countryside is poisoned. Eventually, later in the week, reserve battalions move up to replace the massacred soldiers. Willie is bereft. He makes his way back to the section of trench and amidst the now-grotesque bodies of his comrades discovers the corpse of Captain Pasley. He encounters Father Buckley, blessing the bodies of the dead. The two awkwardly console one another. Over five hundred men of their regiment are dead. Later, Willie (a protestant) politely refuses communion with the priest.

When Willie sees Christy Moran again, he is furious at his sergeant’s brutal assessment of Captain Pasley’s refusal to run. As more men are brought up to the line to replace his comrades, he also begins to have an inkling of the nature of the war.

The survivors see out the summer into the freezing winter of 1916, hearing of more Irish losses at Gallipoli. They are posted away from the front. Willie’s platoon traverse the countryside. His memories of building reviving within him, Willie admires the roads and particularly enjoys singing marching songs, especially the ubiquitous ‘Tipperary’. Willie’s singing voice is admired but has been weakened by his faulty lungs, damaged by the chlorine gas. He also notes the damage to himself. He mourns Clancy and Williams and feels haunted by the ghost of Captain Pasley. The grief of death has lodged within him, and he secretly rails against the world.

Questions

A shocking and moving read, this chapter, as it surely must be if well written.

The stalling of Willie and Gretta’s relationship while Willie fights abroad is perhaps unexpected, given the account of the relationship we read in the first chapter. She is, to use a phrase used in theory, an absent presence at this point in the story. What does the silence of Gretta suggest to you about this couple’s relationship? In what ways might her silence reflect a larger truth about the presence of women in literature of the First World War?

Captain Pasley, who reads Willie’s letters to Gretchen, judges that Willie is one of those soldiers who “tried to write the inside of their heads” when writing home (p.43). What do you think is meant by this? Given the evidence of Willie’s letter to Gretta (p.38), is Pasley’s assessment accurate? How would you describe Barry’s presentation of Willie in this letter? What does it reveal about Willie?

The narration often uses free indirect speech: that is, the voices of the novel’s characters often merge with or are articulated through the voice of the narrator. This creates interesting ways of manipulating and moving between different characters’ perspectives, but inevitably in the story thus far, we have most often presented with the perspective of Willie Dunne. In this chapter, however, the omniscient narrator is used to voice the thoughts of Captain Pasley as he censors the men’s mail (see the paragraph that begins, “Captain Pasley was in his new dugout writing his forms…” (p.42)). Why might the author decide to give the reader access to the thoughts of this particular character at this particular moment in the novel, before the gas attack? In what way is Pasley’s reading relevant, in terms of storytelling, to the events that follow? How effective is this narratological shift of perspective?

Barry’s description of the gas attack is memorable and shocking. He cleverly selects surprising foci in his description of the attack that make it particularly strange and frightening. What does the narrative describe that emphasises the transformation of the familiar world into one completely unfamiliar and peculiarly terrifying?

“All the Irish were on the fire-step now, all along the length of the trench, some fifteen hundred men showing their faces to this unknown freak of weather, or whatever it might be.” Reading this sentence, and the whole of the gas attack sequence (p.43-8), how does Barry create tension within the text?

As Barry builds a sense of scene in this chapter, he returns again and again to the colour yellow— at first “yellow world” of the wild flowers and caterpillars that hang on them, then the “strange yellow-tinged cloud” itself, and finally the “yellow world” that Willie awakes to, with its men wearing bleached uniforms and yellow, greased faces. What could these different kinds of yellowness represent?

“If it were a battle proper, these men would never have turned tail. They would have fought to the last man in the trenches and put up with that and cursed their fate” (p.48). Besides this odd (and surely redundant) bit of moralising narration, Barry is, I think, both clever and subtle in reflecting on a broad sense of shame felt in the aftermath of the attack. Why could a gas attack be seen as particularly shameful in the theatre of war? In what ways does the use of poison gas differ to other more traditional forms of warfare? How do the characters focused on in the novel respond to the trauma of the gas attack?

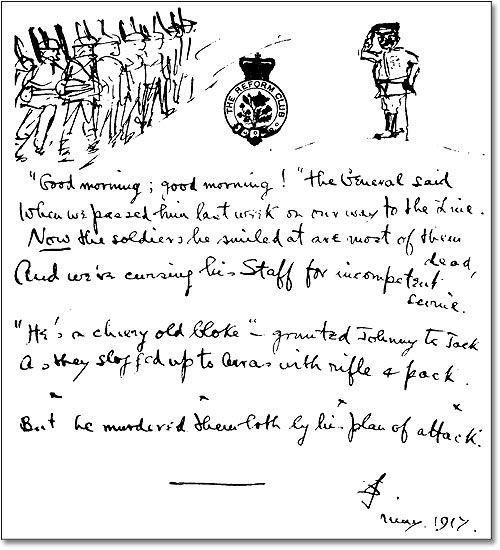

The passage at the end of the chapter, where Willie finds pleasure in singing marching songs like ‘Tipperary’, seems significant to the narrative as a whole. The novel, after all, is called ‘A Long, Long Way’, a metalepsis of the fuller song title, ‘It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary’ (see the entry ‘Opening Lines’ and comments beneath for an explanation of this term). Song, therefore, has meaning in this text (and indeed was ubiquitous in the trenches during the war: see these entries about the Ragtime Infantry and read these poems by Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon and Ivor Gurney.) At the end of this chapter, how does Willie’s singing, and song more generally, cause us to reflect on the gas attack on the Royal Dublin Fusiliers? How significant is it that now, “when Willie sang too mightily he felt a dire need to cough” (p.58)?

Some thoughts

The gas attack in this chapter was exceptionally well written. Before writing an appreciation, it’s best to make clear that I currently have questions about Barry’s presentation of the attack at St Julien. This is presumptuous to a degree— Barry has plainly read deeply around the subject— but I’m still trying marry up elements of the historical record with the movements of Willie’s company.

On first reading, I had assumed that the gas attack depicted in the book is the gas attack of the early evening of 22nd April 1915, the beginning of the Battle of Gravenstafel Ridge, itself the first battle of the murderous Second Battle of Ypres. I thought this because this was indeed the first German gas attack of the First World War, and the absolute incomprehension of the Irish troops in the face of the new weapon depicted in the book is more readily explicable than it would be in any depiction of the later gas attack of the 24th May, when the Royal Dublin Fusiliers were massacred. The April attack took place, as depicted in the novel, during the day-time: moreover, there was an Irish presence in the line during the attack of the 24th, the Royal Irish Fusiliers being positioned north of Wieltje, though not in a position that precisely reflects that described in the novel.

The attack of the 24th May 1915 is the more likely source of the massacre described in the novel: 666 men of the second battalion of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers’ were in the line that day, and of that number, 645 men died. This chimes with Willie’s observation that there were “five hundred men and more of Willie’s regiment dead” (p.53). Crucially however this gas attack took place at night, at 2.30 in the morning, quite unlike the attack described in the book. The question that presents itself, then, is what Irish battalion Willie is part of? Willie’s first letter home in the book gives as his address the “Royal Dublin Fusiliers… Fermoy” (p.16) yet even with joining up in August 1914, and training in Fermoy in December of that year, I can’t see how Willie would have seen action at all near St. Julien in May (as far as I can discover, the second battalion of the RDF was moved from Harrow to Bolougne in August of 1914).

I’m assuming that I’m missing something important here, and I’d appreciate any pointers from military historians as to how to make sense of Barry’s timeline in the novel. Of course, some might say that I’m making a category error here in bothering about this stuff. It’s fiction, you know? I think these things do matter in understanding a novel, however. If Barry has decided to conflate these two attacks, then he has done so with a purpose. That purpose would be well worth speculating on, especially as the presentation of the gas attack is so effective, so moving, so shocking. If however, I’m simply short of information, then that of course is well worth knowing too.

I don’t want to speculate on what is probably a matter of my own ignorance. The gas attack depicted in the novel may be historically accurate and it may not be. Indeed, the virtues of historical accuracy can weigh against the virtues of drama or plot or authorial intention, and art is one of the only pursuits in which we can say without blushing that sometimes by making things up we can get closer to the truth of things. Yet interesting ethical and aesthetic questions are opened up here regarding the lengths of literary invention desirable or permissible in writing a historical novel (as alluded to in my earlier post on the novel form).

Especially, I want to say, when reading something as convincing as Barry’s gas attack. What a piece of writing it is.

The great risk in writing about a First World War gas attack is to fall into cliché and simply retread where others have gone before. Two British works of art overhang any depiction of gas warfare during the first world war; Wilfred Owen’s ‘Dulce et Decorum Est’, of course, and John Singer Sargent’s ‘Gassed’. Both are referenced in Barry’s account of the St. Julien attack: in his description of “faces [that] were contorted like devils’ in a book of admonition” and the “long lines of men going back along the road, with weird faces, their right hand on the shoulder of the man in front”. A-level Literature students should as a matter of course read Owen’s and Barry’s texts together here, exploring their commonalities and differences.

Yet it seems to me that Barry’s creation stands well clear of the shadow of these more famous texts, and, by mark of its invention, to signal towards texts both more marginal and imaginative. In terms of the A-level exam, I would also want to explore the narrative strategy found in Robert Frost’s ‘Range Finding’ to explore how Barry uses the presentation of the natural world to momentarily decentre the human experience of war. Nature, it seems plain, is both a consolation and a source of grief in Barry’s novel, as it was for many of the poet-soldiers of the First World War. Its fecund life and beauty is a counterpoint to the ugly, wilful and mechanical destruction of man. The horror of the foaming caterpillars, fizzing grass, dying trees and silenced birds in the path of the chorine gas speak quite as loudly of the directionless violence of man’s death-dealing as does Barry’s horrifying description of the massacre of the fusiliers.

Another text I felt at the edge of Barry’s reference, peculiar though it may seem to some, is HG Wells’ ‘The War of the Worlds’ (1898). Peculiar because Wells’ story of an invasion of Earth by aliens from Mars might seem, at first blush, an irrelevance to Barry’s staunchly realist text. Yet Wells’ novel was one of the first to imagine such devastating gas attacks: Wells’ invading Tripod machines drop asphyxiating ‘black smoke’ over the cities and towns of Southern England in their march on London. Now, Jules Verne imagined a freezing gas used in artillery shells by dastardly Germans in his 1879 novel ‘The Begum’s Fortune’: but it is the message regarding imperialism that is made explicit at the start of Wells’ novel that I feel makes it peculiarly relevant to Barry’s novel. The narrator, who has lived through the Martian invasion, takes to task those who complain of the inhumanity of the invaders:

And before we judge of them too harshly we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and the dodo, but upon its inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

It strikes me that the political roots of warfare are understated in the novel thus far, as the author focuses on the personal experience and horror of war. Yet in this description of the supposed inhumanity of the alien invaders and their deadly technology, Wells performs a similar trick to Barry. Colonialism and Imperial Wars—human pursuits, of which the First World War is a prime example— are refigured as assaults from beyond earthly nature, beyond humanity. Both writers manage to make the precarious empire of man both utterly strange and frightening. Indeed, I want to say that the gas cloud in chapter four is one of Barry’s most memorable characters yet: a “dark and seemingly infernal thing creeping along”, the disowned monster of the terrible and grasping intellect of man.