Gretta Lawlor is a young Dublin woman, first introduced into the story as the daughter of Mr Lawlor, a man beaten by Metropolitan Policemen under James Dunne’s charge. Willie delivers pheasants on behalf of his guilty father to Mr Lawlor, and in delivering these he encounters Gretta as a thirteen-year-old girl. She is a particular Dublin beauty, “truly… one of the beauties of the city”, though like other Dublin beauties, she is “skinny and destitute”. Gretta is a working-class girl, living in a tenement beneath the city’s Protestant cathedral, and this establishes an initial difference between the two that means they conduct their relationship in secret. Willie is aware that his own family’s middle-class snobbery means that he “he knew what Maud and especially Annie thought about such things, and they would immediately tell his father”, so that their relationship “wasn’t normal or straight exactly”. In this way, Gretta’s relationship with Willie is defined by the same reticence to challenge his family’s worldview that later becomes such a source of contention and grief in the novel.

Willie from the very first falls head over heels in love with Gretta. His worshipful devotion to her stands in strong contrast to Gretta’s own manner of loving. Gretta is from the first a composed and resolute figure who finds value in her father’s dictum that a man should know his own mind, though she holds these words in some ironic distance: “that’s only a thing he got out of a little book he reads. St Thomas Aquinas Willie. That’s all.” The narrator writes that “Gretta was an extremely straightforward person and she knew herself when she saw Willie for the first time that Willie was for her”, and indeed where Willie is sometimes all sentiment and emotion, Gretta is an unsentimental source of clarity in the novel. She is clear from the first about what she wants and expects, and Willie’s attempt to enlist is “much against Gretta’s desires”. She has a practical insight that Willie often lacks. Later, when her expectations of Willie are disappointed, she makes new plans.

Despite her age, Gretta is a mature presence in Willie’s life, and her seriousness and pragmatism stand in strong contrast to Willie’s own romantic and idealistic nature. Indeed, Willie proposes to Gretta “but she had not felt awkward saying no.” She answers, Willie observes, “like a lawyer”. There is indeed a firmness that can be almost stern, as when Willie reintroduces the matter on furlough, and she “surprisingly shook a finger at him”. Where Willie would give into sexual desire and emotion, Gretta shows judgement and control. The two have a relationship in which the one is mindful of the other (“though they could row like the best”) but in wry, ironic phrasing, the narrator observes that “she wasn’t so wedded to the idea of his erection as perhaps he was”. When Gretta decides to make love to Willie before he returns to Flanders, she controls the encounter, for “she drew him into the deeper dark” by the canal-side, and “she drew up her skirt in the greeny dark”. She will not commit to marrying Willie until after the war, but she does show deep affection for Willie.

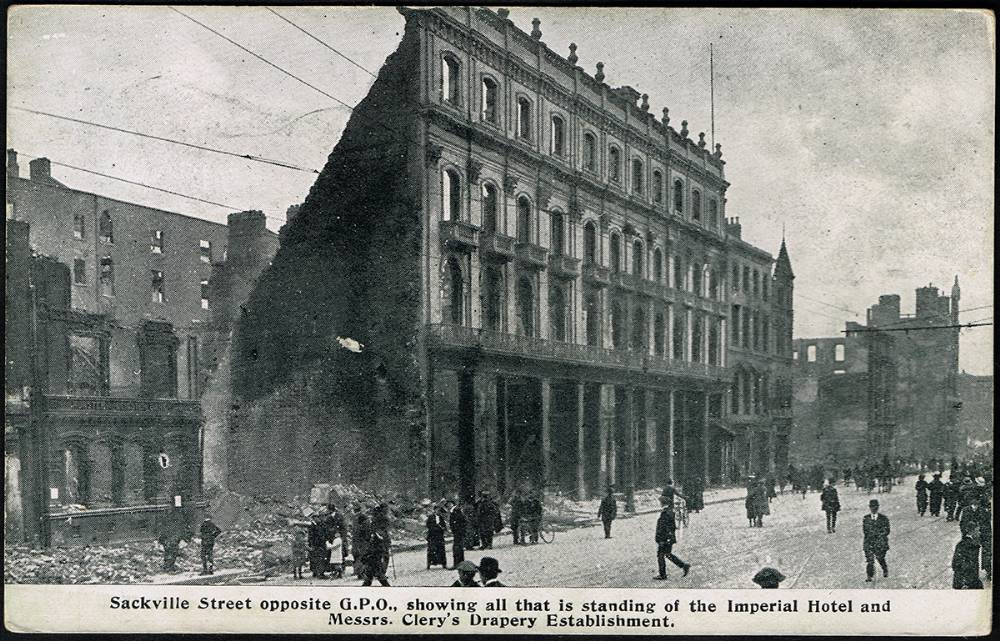

Gretta is at times a seemingly distant lover, who does not reply to Willie’s letters, and this is a problem for Willie throughout the novel. Admitting this, Gretta nonetheless gives her own reasons for this lack of communication- “I’m tired in the evening when I get home and have to make a supper and then I just sit in my chair like a ghost or fall into the doss.” Her relentless work as a seamstress, then, is an important influence on Gretta’s life, and indeed her “bossman Casey” is “like a bishop when it comes to his women courting”. Gretta’s life— the time she can call her own, the relationships she can be allowed to have— is dictated by her exhausting life as a working class woman. There is, nonetheless, a matter-of-factness, a certain disregard for Willie’s intensity of feeling that is both sad and inadvertently funny about Gretta’s thoughtless communication: as when she sends him, as Willie puts it, a “kind and interesting postcard showing Sackville Street in ruins- who would ever have thought- thinking of you”. Unsurprisingly, given their age and relative inexperience in relationships, both Gretta and Willie are guilty of a kind of thoughtlessness that is not related to the intensity of feelings each has for the other. They find it difficult to maintain their relationship through the separation caused by the war.

Gretta remains Willie’s first and only girlfriend, though he betrays her trust in sleeping with a prostitute in Amiens and this ultimately leads (after Gretta reads Pete O’Hara’s secret letter) to the break-up of their relationship, a devastating blow to the young man. When, at the end of the book, Willie returns to Dublin and visits Gretta, he finds her breastfeeding the baby she has had by her new husband. Gretta writes a letter to Willie in response to O’Hara’s, but it never reaches Willie. Gretta is conscious of her betrayal but she is understanding as they say goodbye to one another: “I don’t suppose it was such a very terrible thing you did, but it broke my heart to read it.” The relationship ends with this tone of sadness and regret.

In the totality of the novel, we encounter Gretta in relatively few scenes, as the narrator follows the twists and turns of Willie’s short life. As Willie’s first love, the image he holds of her is vital to his character, and the thought of her sustains him through his many trials. We see Gretta in the text most often through the lens of Willie’s affections and frustrations, and in this sense the novel is as centred on a masculine viewpoint of the war, seen from the front line, as many of the other texts that have been written about the First World War. Yet, as the practical and forthright working-class Irishwoman who is Willie’s young lover, she offers glimpses in the novel of another Irish perspective on the war.